-

|

|

|

|

Development

of the

Chronomatic Movements

(Caliber 11, 11-I, 12 and 15)

|

|

Ask

any vintage chronograph enthusiast what

happened on March 3, 1969, and he will

answer you quickly and with certainty,

"That was the day that the Heuer,

Breitling, Hamilton-Buren,

Dubois-Depraz partnership introduced

the world's first automatic

chronograph, with press conferences in

Geneva and New York City".

Ask

Hans Schrag (then Heuer's head

watchmaker in the United States) what

happened during the afternoon of March

3, 1969, just hours after the New York

City press conference, and he will tell

you of another memorable event, "That

was the time when the world's first

automatic chronograph came into the

service department for the first repair

of an automatic chronograph." Press

Hans for details, and some forty and

one-half years later, he will tell

describe for you the look of

disappointment from the owner of the

watch, the exact position of the

malfunctioning 8140 operating lever,

and his own shock to see an automatic

chronograph (and especially the oddity

of the crown at nine o'clock). Of

course, the owner of the watch was also

disappointed: he had won the watch in a

drawing at the New York City press

conference, but this marvelous new

watch didn't even make it to the end of

the afternoon before

malfunctioning.

Indeed,

it was the amazing speed with which the

Caliber 11 movement was developed that

allowed the Heuer-Breitling venture to

win the race to introduce this

horological marvel; this same speed

also resulted in a movement that

required immediate modification and

improvement.

This

webpage tells the story, not of how

Hans Schrag repaired the world's first

automatic chronograph -- that is

another story for another day -- but of

how the Caliber 11 series of movements

was developed and improved, beginning

in March 1969, to become a reliable

workhorse for a generation of amazing

chronographs.

|

|

|

|

Jeffrey

M. Stein

November 6, 2009

Copyright

Jeffrey M. Stein, 2009, all rights

reserved

|

|

|

|

Thanks

to Hans Schrag for providing the

technical and historical information

that allowed me to create this webpage;

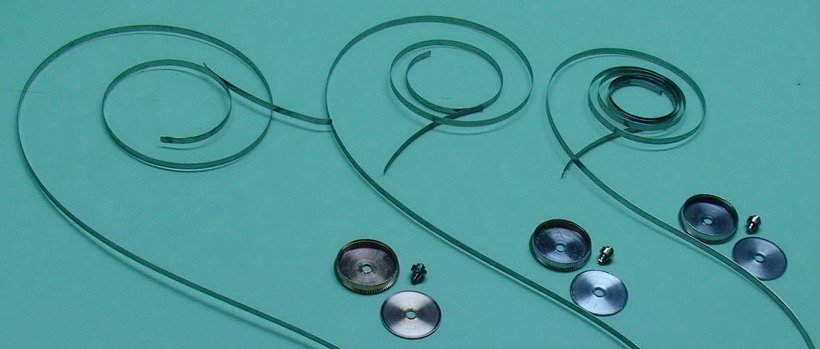

thanks also for providing the three

chronograph modules show at the top of

this page. As I keep reminding

Hans: The more information he provides

for these sorts of webpages, the less

we will need to bug him with our dumb

questions (and the more he will enjoy

his retirement)!

Thanks

to Abel Court for providing many of the

photographs that illustrate this page,

and for helping me puzzle through so

many of the mysteries of the

Chronomatic movements. Never before has

the bi-metallic oscillating pinion been

photographed so

beautifully!

Thanks

to all the readers, writers, bloggers,

photographers, illustrators, dealers

and collectors who comprise the

OnTheDash / Chronocentric community.

Your passion inspires these

projects.

|

|

|

|

Background

of the Chronomatic Movements (Caliber

11 / Caliber 12)

As

described in our previous articles

about the development of the

Chronomatic (Caliber 11 / Caliber 12)

movements, the joint venture of Heuer,

Breitling, Buren and Dubois-Depraz "won

the race" to market the world's

first automatic chronographs, when the

Chronomatic chronographs were

introduced in March 1969 and offered

for sale to the general public during

the Summer of 1969. The Caliber 11

movement was an entirely new movement,

developed on a "white board" basis

by the joint venture partners, and in

order to win the race to market, the

movement was designed and developed

very quickly. In addition to the

innovation of being the first automatic

chronograph, the Caliber 11 had several

advanced technical features. In view of

the nature of the joint venture, the

speed with which the movement was

developed, and the technical features

of the Chronomatic watches, it is not

surprising that the Chronomatic watches

suffered from a variety of technical

issues when they were first sold to the

public.

This

webpage tells the next chapter of the

story -- how the Caliber 11 movements

were developed and improved after their

introduction in 1969, to become the

popular movements that powered a new

generation of chronographs for Heuer,

Breitling, Hamilton, Bulova, Zodiac and

several other brands. We will see that

while the Chronomatic partners lacked

the luxury of fully developing this

movement prior to its introduction,

they continued to develop these

movements so that they were the

workhorse movements of the 1970's and

continue as reliable movements, 40

years after their

introduction.

Caliber

11 -- The Early Problems

Some

of the technical problems arose with

the Caliber 11 movements arose from

decisions made in designing the

watches; others arose from poor

engineering or a lack of development of

the movement, as the partnership

competed to bring the first automatic

chronograph onto the market. The

following were among the most

significant design features of the

Caliber 11 movement, along with the

"technical" problems which were

attributable to these

features:

- Jumping

Hours. While most chronographs

of the period utilized a

“jumping” minute recorder

(meaning that the minute needle

jumped every minute) and a

“creeping” hour recorder

(meaning that the hour needle moved

continuoously during the hour), the

Caliber 11 used a jumping hour

recorder as well as a jumping minute

recorder. Accordingly, the hour

needle "jumped" every 30 minutes,

rather than moving continuously.

Having both the minute and hour

needles "jump" in one instant

required incrementally more power

than having the hour needle creep on

a continuous basis.

- Jumping

Date. The Caliber 11 was also

designed so that the date disk would

"jump" in a relatively short period

of time (beginning at 11:45 p.m.),

rather than beginning to change

earlier in the evening (for example,

at 10:30 p.m.). This jumping date

disk also required incrementally

more power than a disk that would

move more gradually over the course

of a longer period. Combined with

the jumping minutes and hours, the

movement required considerable power

to "jump" the date disc in only

15 minutes between 11:45 and

midnight.

- Banking.

In order to provide the power that

would be required for the Caliber 11

to operate -- with the chronograph

running, the needles jumping, and

the hour disk changing within a

relatively short period of time --

the Caliber 11 required a strong

mainspring. The mainspring used for

the Caliber 11 turned out to be too

strong, resulting in the problem of

"banking" (or

“rebanking”), meaning that

the balance wheel had too much

amplitude and caused the watch to

run too fast.

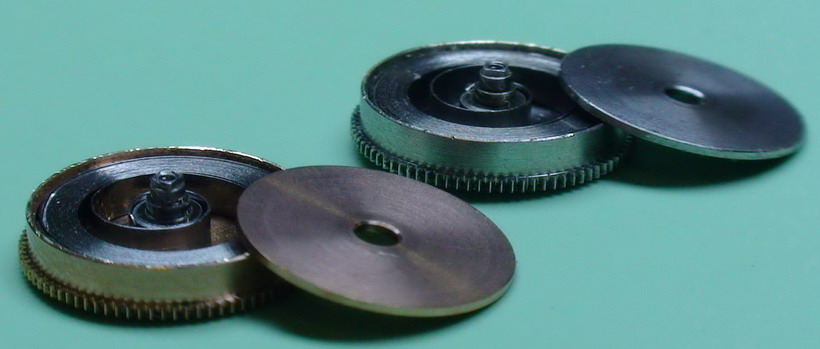

- Bi-Metallic

Pinion. The oscillating pinion

used in the Caliber 11 movement

(8086) was "bi-metallic", with a

brass head on a steel shaft. (The

Heuer-Breitling-Hamilton group used

a bi-metallic pinion, because at the

time that the Caliber 11 movement

was being developed, the group did

not have the ability to manufacture

a one-piece, all-steel pinion).

Becuase the head of the oscillating

pinion engages with the chronograph

runner wheel (8000) every time the

chronograph is started (and

disengages every time the

chronograph is stopped), there were

concerns that the pinion and wheel

would wear out prematurely.

The

Caliber 11-I Movement

As

a result of these technical problems

with the Caliber 11 movement, within a

year of its introduction, the

Chronomatic group

(Heuer-Breitling-Hamilton) made the

changes that resulted in the creation

of the Caliber 11-I movement. (We are

not certain, but can assume that the

"I" designation indicated that the

movement had been "Improved".) Changes

from the original Caliber 11 to the

improved Caliber 11-I included the

following:

- Creeping

Date Change. The date indicator

driving wheel (jumper) (2556) was

redesigned, so that the date changed

more slowly. On the Caliber 11-I,

the date change would begin at 10:30

p.m. and occurred over the next 90

minutes, with a "click" at

midnight.

- Lighter

(Weaker) Jumper Springs.

The jumper springs on the minute

(8270) and hour (8705) recorders

were made lighter (weaker), so that

less power was required for the

needles to jump each minute and each

30 minutes.

- Weaker

Mainspring. With less power

required to drive the date wheel and

the chronograph needles, the Caliber

11-I used a weaker mainspring than

the Caliber 11. (The improved

Caliber 11-I mainspring was housed

in a nickel-plated barrel, whereas

the Caliber 11 used a rose-colored

barrel). Changes in the balance

wheel also addressed the problem of

"banking".

- All

Steel Oscllating Pinion. The

oscillating pinion (8086) was

changed from being bi-metallic

(steel and brass) to solid steel. In

addition, the chronograph runner

wheel (8000), which mated with this

pinion, was changed from brass to a

nickel-silver alloy.

The

Caliber 12 Movement

Changes

from the Caliber 11-I movement to the

Caliber 12 movement included the

following:

- Faster

Beat. The "beat" of the

movement was changed from 19,800

vibrations per hour (VPH) in the

Caliber 11 and 11-I, to 21,600 VPH

in the Caliber 12. The change to a

higher beat was consistent with

trends in the watch industry,

suggesting a preference for higher

beat movements. The change in the

"beat" of the movement required

a re-design of the mainspring and

balance wheel, as well as

corresponding changes in the fourth

wheel (225), the escape wheel and

pinion (705) and the pallet

fork and staff (710). These

components are unique to the Caliber

12, and earlier parts for the

Caliber 11 or 11-I may not be

interchanged with these parts.

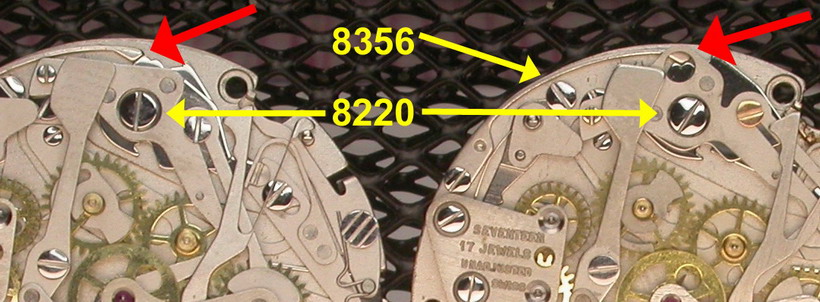

- Strengthening

Other Components. Certain

components of the Caliber 12

movement were made stronger or

otherwise improved. For example, the

fly-back lever (8180) was made

wider, as the narrower levers on the

Caliber 11 and 11-I had sometimes

failed. One of the most visible

changes from Caliber 11-I to Caliber

12 was in the reshaping and

enlargement of the hammer (8220). In

the Caliber 11 and

11-I movements, the hammer cam

jumper (8356) rested against

the lower section of this hammer

(8220), but there was nothing to

prevent the hammer cam jumper (8356)

from "jumping" out of position,

coming to rest above the hammer

(8220), which would result in the

start / stop / reset being

inoperable. In the Caliber 12

movement, the "head" of the

hammer (8220) was made

significantly larger, so that it

"sandwiched" the hammer cam

jumper (8356) in place and prevented

it from jumping out of position. A

large hole in the head of the hammer

(8220) allows for oiling of the area

of contact between the jumper and

the hammer, and is an easy way to

identify a Caibler 12

movement.

- Color

Change. The most visible change

from the Caliber 11 and

11-I movements to the Caliber

12 movement was that the main plates

of the movement were changed from a

nickel / silver color to a gold

tone. The Caliber 12 looks like a

gold tone movement, compared with

the silver tone of the Caliber 11

and 11-I. (There are, however,

certain Caliber 12 movements that

use the same nickel-silver plates as

the Caliber 11 and 11-I. In these

instances, the "11" on the

chronograph bridge (8500) is

over-stamped with a

"12".)

The

Caliber 15 Movement

In

order to be able to offer their

automatic chronographs at lower prices,

in 1972 Heuer and Breitling modified

the Caliber 12 movement so that it was

offered as the Caliber 15 movement. The

most obvious difference between the two

movements is that the Caliber 12

movement has a 12-hour recorder and a

30-minute recorder, whereas the Caliber

15 movement has only the 30-minute

recorder. [mention re running

seconds at ten o'clock] In addition

to the deletion of the 12-hour recorder

-- which saved considerably in the cost

of parts and labor -- the following

changes from the Caliber 12 to the

Caliber 15 allowed the Caliber 15 to be

produced on a more economical

basis:

- Brass

Balance Wheel (rather than

Glucydur). The Caliber 12

movement used a Glucydur balance,

while the Caliber 15 movements used

a brass balance. Glucydur is an

tradename for an alloy made of

berrylium, copper and iron. This

material features excellent hardness

and high stability over a range of

temperatures, and is resistant to

deformation or damage.

- KIF Shock

Protection (rather than

Incabloc). The Caliber 12

movement used the Incabloc shock

protection system, whereas the

Caliber 15 movement used the

KIF system. The primary

difference between the Incabloc and

KIF shock protection systems is

in the shape of the spring which

holds the cap jewel in place; both

springs are hinged so that the jewel

can be removed without removing the

spring.

- Deletion

of Isochron Regulation

(Micro-Regulation). The Caliber

12 movement used the Isochron micro

regulation system, which derived

from the regulation system used in

the Buren Intramatics. The Isochron

system uses two sets of eccentric

screws and forked levers to move the

regulator (307/1) and the hairspring

stud (364) with great accuracy. This

system allows the adjuster to put

the watch into near perfect beat and

regulation without many frustrating

back and forth movements of the

regulator (curb pins) and stud

carrier. This regulation system is

not used on the Caliber 15 movement,

making it more difficult for the

watchmaker to regulate the watch

accurately.

The

use of the Caliber 15 movement rather

than the Caliber 12 movement allowed a

Caliber 15 Carrera to have a retail

price of $170 (versus $185 for the

Caliber 12 model); the Cal 15 Autavias

were priced at $185 (versus $200); and

the newly-introduced Calculator

retailed for $200 with the Caliber 15

(versus $220 for the Caliber 12 model).

[add re Monaco]

|

The

following table summarizes the primary

differences between the Caliber 11, the Caliber

11-I and the Caliber 12 movements, as described

in more detail above.

|

|

Caliber

11

|

Caliber

11-I

|

Caliber

12

|

|

Period

of Production

|

from

March 1969

until late 1969

|

from

late 1969

until 1973

|

from

late 1971

until 1980

|

- Easiest

Ways to Distinguish Caliber 11 /

Caliber 11-I / Caliber 12

Chronographs

|

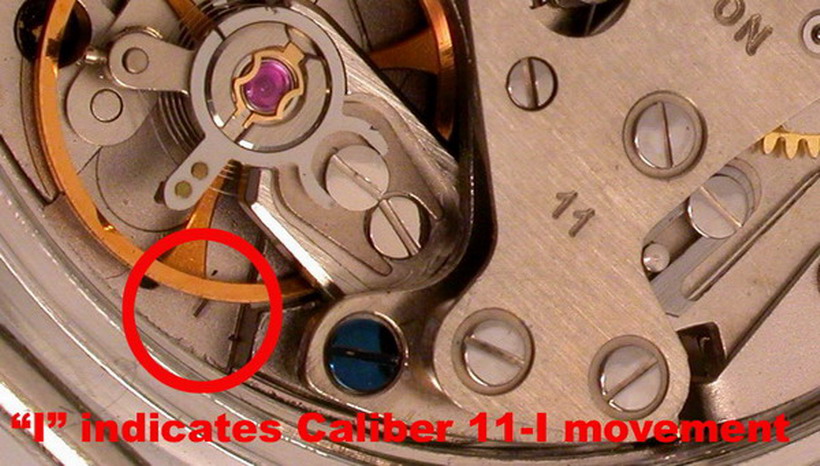

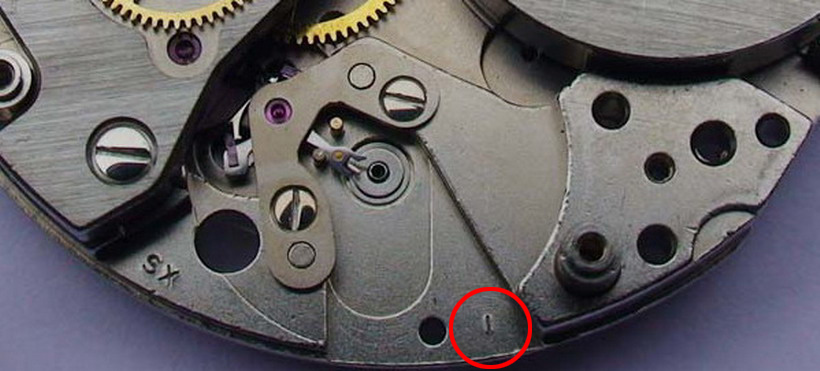

- Marking

on Movement

|

Cal

11 on chronograph bridge

(8500)

|

Cal

11 on chronograph bridge (8500);

small "I" under balance

wheel

|

Cal

12 on chronograph bridge

(8500)

|

- Color

of Main Plates

|

nickel

silver

|

nickel

silver

|

gold-colored

(usually)

|

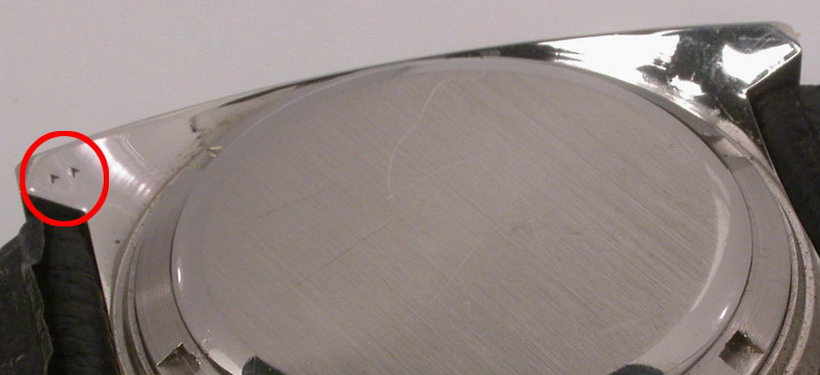

- Marking

on Case

|

no

special mark

|

small

star or arrows on back of one

lug

|

no

special mark

|

- Date

Change

|

jumping

(starts at 11:45)

|

gradual

/ creeping (starts at

10:30)

|

gradual

/ creeping (starts at

10:30)

|

- Beat

(vibrations per hour /

VPH)

|

19,800

VPH

|

19,800

VPH

|

21,600

VPH

|

|

Major

Changes in Parts of the Movements

|

|

Minute

and Hour Jumper Springs

|

heavier

(stronger)

|

lighter

(weaker)

|

lighter

(weaker)

|

|

Color

of Barrel

|

rose

|

nickel-plated

|

nickel-plated

|

- Oscillating

Pinion

|

bi-metallic

(steel and brass)

|

all

steel

|

all

steel

|

- Chrono

Runner Wheel

|

brass

|

nickel

/ silver alloy

|

nickel

/ silver alloy

|

- Hammer

(8220)

|

smaller

|

smaller

|

larger,

with hole for oiling

|

Some

notes regarding these movements:

- The

"periods of production" for the Caliber 11,

11-I and 12 movements are not precise,

and there is overlap in Heuer's use of the

movements. For example, the Caliber 12 was

introduced late in 1971, but many Viceroy

Autavias (Ref 1163V) produced in 1972 and

1973 continued to use the Caliber 11-I

movements. Accordingly, we find otherwise

identical chronographs from this sort of

transitional period with both the Cal

11-I and the Cal 12

movements.

- We

say that the main plates of the Caliber 12

movement are usually gold-colored, but there

are Caliber 12 movements that use the nickel

silver plates from a Caliber 11 or

11-I movement. In these instances, we

see that the "11" on the chronograph has

been "blanked" and a "12" marked in

place of the "11". Such renumbered Caliber 11

bridges, in the nickel silver color, do not

seem to be transitional, but were also used

later in the production of the Caliber 12

movement.

|

|

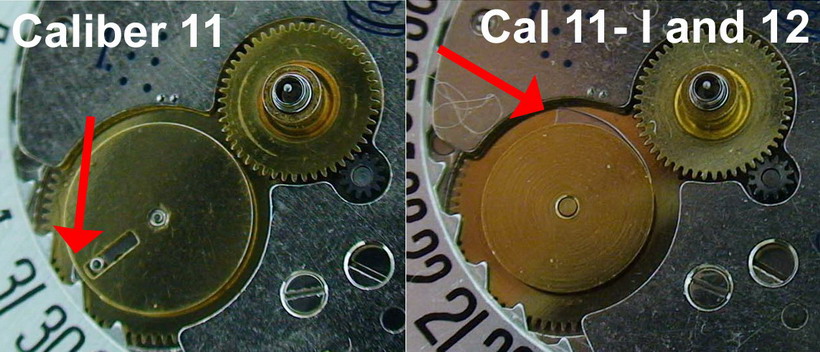

Caliber

11-I has Special "I" Mark under Balance

Wheel

|

|

|

Caliber

11-I has "Arrow" Marks on Back of

Lugs

|

|

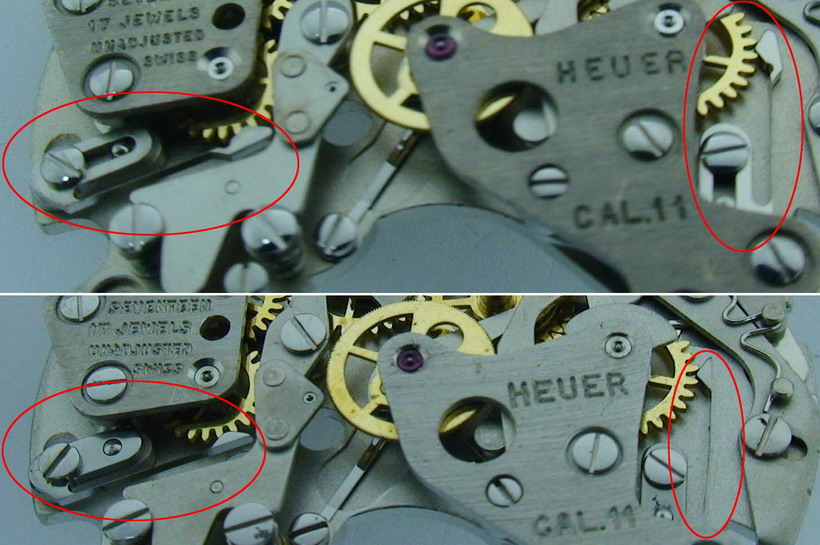

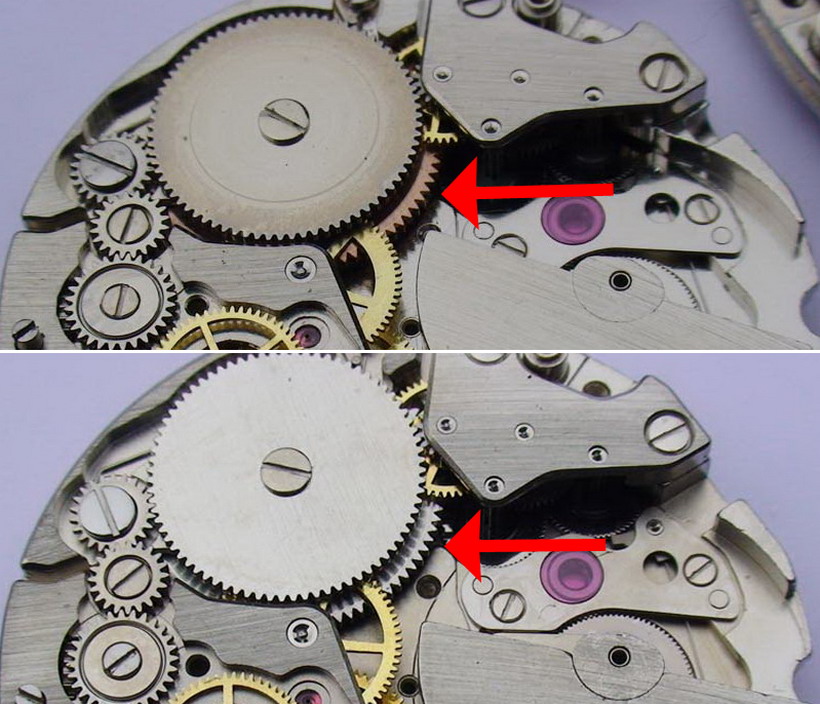

Jumper

springs (8270 and 8705) are larger

(heavier) on Caliber 11 (above);

smaller (lighter) on Caliber 11-I and

Caliber 12 (below)

|

|

Date

indicator driving wheel (2556) provides

for rapid date change on Caliber

11;

slower, more gradual date change on

Caliber 11-I and Caliber

12

|

|

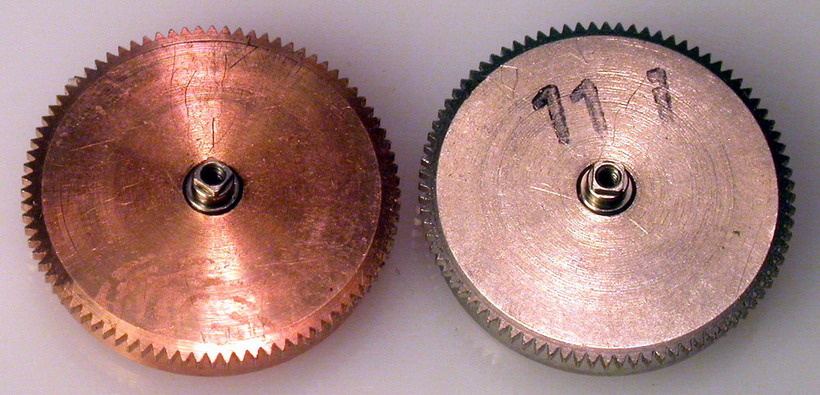

Barrel

(180) is rose colored on Caliber 11

(above and left);

nickel-plated on Caliber 11-I and

Caliber 12 (below and right)

|

|

Mainspring

in the Caliber 11 is too strong (which

contributed to banking);

mainspring in Caliber 11-I and 12

is weaker, so that watch keeps proper

time

|

|

|

Oscillating

Pinion

|

|

|

The

hammer (8220) in the Caliber 12 was

redesigned and enlarged, so that the

hammer cam jumper (8356) is held in

place between the "head" of the

hammer (8220) and the main chronograph

plate (8281). The hole in the head

allows for oiling.

|

|

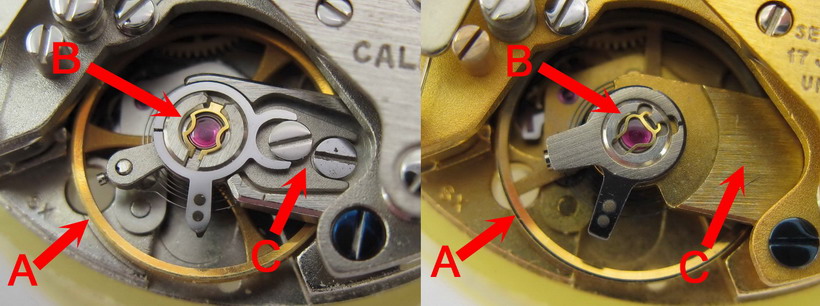

|

Three

differences between the Caliber 12 and

the Caliber 15 include, (A) the Caliber

12 uses a Glucydur balance, and the

Caliber 15 uses a brass balance, (B)

the Caliber 12 uses Incabloc shock

protection, and the Caliber 15 uses a

KIF system, and (C) the Caliber 12

has fine (micro) tuning in its

regulation (through two screws on the

balance bridge), and the Caliber 15

does not provide for micro

regulation.

|

|

|

|

|

Last

Updated: 2009.10.07 JMS

|

|